Ubisoft sues Apple and Google – another episode of clone wars

![]()

Recent days have brought us another interesting news in the video games industry. Media report that Ubisoft sued Google and Apple. The case concerns a mobile game called Area F2, made by Chinese developer Ejoy.com, which belongs to the Alibaba company. According to the lawsuit, the mobile game is a “carbon copy” of popular Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six: Siege game, released on consoles and PC. Ubisoft’s statements are hard to deny – the similarity is striking. In this article I will present, which legal arguments could be used by Ubisoft against Chinese developer and why we see Apple and Google on the defendants side and not Ejoy.com and Alibaba.

Games cloning is a phenomenon which has existed almost as long as the video game industry itself. There are numerous cases of games being blatant copies or imitations of popular titles. First disputes regarding such games appeared as early as in the ‘70s and are related with the legendary game Pong. Nowadays, the problem of clones is particularly noticeable on the mobile games market. Lower costs of production, as well as easier and cheaper process of releasing games on Google Play or AppStore have caused these marketplaces to be flooded with games openly “inspired” by other popular titles.

Copyright

Games cloning is an issue particularly complex to address from copyright’s point of view. The border between legal inspiration and illegal infringement is very fluid. Copyright does not give protection to ideas, methods or rules. Only specific, creative expression of an idea is protected. Therefore, copying the mechanics of one game in another does not infringe copyright as long as no protected elements of the game are copied, such as art, music, assets or source code.

Not every element of the game normally protected by copyright will be protected in a particular case. It may turn out that apart from the mechanics of the original game, the creators of the clone only copied elements typical for the genre, such as first-person view in the shooter or spellcasting in the fantasy game. These elements are not usually protected by copyright. In the US, such elements are known as scènes à faire, elements almost mandatory in a particular genre. In Poland, we would probably recognise such elements as not creative because of their prevalence in numerous works.

Other intellectual property rights

Other intellectual property rights may be more appropriate to protect a video game from cloning. Clone creators often use similar or even identical names and icons for their productions to lure the consumer to their game. One way to protect yourself against such practice may be to register the name of the game, its logo or icon, and even the names and images of game characters as trademarks. This may effectively discourage cloning or provide for an easier way to prove an infringement in a case when a clone is created. If the game mechanics are truly innovative, it is also worth to consider registering them as a patent (this is what Techland has done with the movement mechanics in Dying Light).

Unfair competition

In a situation when clone developers have not infringed upon copyright or any other intellectual property rights, there is one more legal weapon in clone wars – unfair competition law. Release of the clone may be considered as an act of unfair competition. Clones often try to mislead the consumer that the game comes from a developer which is particularly renowned on the market, either by misleading label on the platform or by passing off. Such behaviour is prohibited. The developers of the original game are entitled to claims for stopping the infringement, remedy, damages or a declaration of an infringement from the clone developers.

The liability of Apple and Google

Based on the rules of the liability of clones’ developers and publishers for infringing rights of game developers and publishers why then in the case of Area F2 Ubisoft sued Apple and Google, not Ejoy.com and Alibaba?

Apple and Google are Internet service providers, AppStore and Google Play respectively, which enable users to buy or download for free games (in this case, clones) directly from their platforms. According to reports, Ubisoft has sent notices to both companies, demanding the takedown of the game from their services. Tech giants did not react to the French publisher’s demands. According to the US Digital Millennium Copyright Act (analogous act in Europe is the so-called e-commerce directive), in case of no reaction to the notice regarding takedown of copyright-infringing materials (e-commerce directive is not limited only to copyright infringements), Internet service providers are liable for the infringement like the direct infringer French publisher probably hopes for the lawsuit to force the giants to react to the emergence of such clones in the future.

Clone wars – a battlefield report

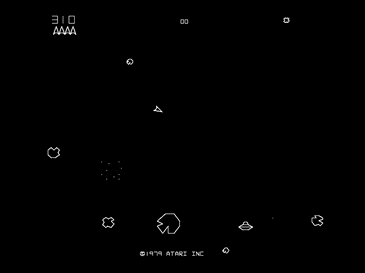

As I mentioned in the introduction, disputes regarding clones have been present in the US almost from the beginning of the video games history. At the beginning of the’80s there was a dispute regarding the cult arcade game– Asteroids. The company called Amusement World created, in the opinion of its author, Stephen Holniker, a superior copy of the game, called Meteors. Atari, the publisher of Asteroids, saw Meteors at the trade fair and decided to file a lawsuit against Amusement World for copyright infringement. To a surprise of many, Atari suffered a defeat. Thanks to this case we got a precedent ruling that the idea for a video game is not protected and as long as there is no copying of particular protectable elements of the game, there is no infringement. The decision in this case opened the doors for the creation and publishing of copies of famous video games. For decades, courts have not really departed from the argumentation presented in this judgement.

Asteroids (left) and Meteors

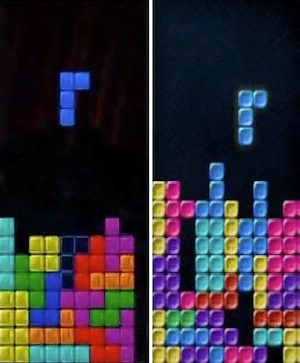

Chances for a change have appeared at the turn of the first and second decade of the 21st century. The case that expressed a different approach to games cloning concerned a different legend – Tetris. In 2009 a company called Xio published a Tetris clone – a game called Mino. Xio’s production was indistinguishable at first sight from Tetris, even though all its elements which were protected with copyright– art and sounds – have been substituted. Deviating from the accepted practice, the court decided to make an overall assessment of the “impression” that a clone makes on its recipients. Following the court’s line of reasoning, it is therefore not enough to make minor changes to the original to avoid liability for video game’s copyright infringement.

Tetris vs Mino (source)

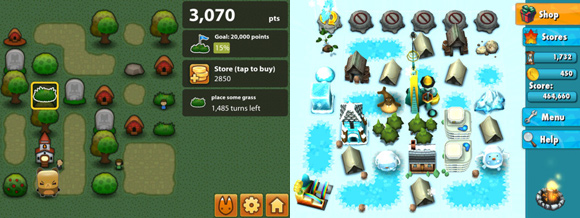

Similar conclusions can be drawn by looking at Spry Fox v. 6Waves case. The dispute concerned a game called Yeti Town, which copied the game mechanics of a title called Triple Town, however significantly changed the art and setting of the game. Although the case has ultimately ended with a settlement, the court’s decision which allowed for the trial suggested a similar approach as in the case of Mino game. The court has drew his attention not only to the protected elements of the game, but also to the game mechanics and the impression of the recipients, supported by bloggers’ opinion who have pointed out the striking similarity between both titles. The decision of the court has been also influenced by the name of the disputed game and the fact, that the publisher of Yeti Town was initially supposed to publish Triple Town at social media platforms, but the negotiations between the parties have failed.

Triple Town vs Yeti Town (source)

Summary

Games cloning is a morally wrong, but incredibly lucrative business and unfortunately it does not seem like it could end soon. Clone developers save time on the process of designing games, which allows them to make quick money. Clones may sometimes even be used as a tool for defrauding personal information or offences against minors, which has been shown by recent example of Club Penguin clones. Apple and Google, as the “gatekeepers’ of their ecosystems do not want to create an image that it is hard for developers to access their platforms, which could discourage devs to create games for their platforms.

It is hard to tell what would be the final result achieved by Ubisoft in a case which has become an inspiration for publishing this article. Proving a copyright infringement, which is required for tech giants’ liability might be very hard. For sure, the publisher counts on a similar outcome as in the Triple Town case. As in the case of this simple game, the cloning is evident, and the opinions of Internet users are unequivocal. No matter the end result, Ubisoft has managed to score a first win – Ejoy.com decided to delist the Area F2 from App Store i Google Play to „carry out improvements in order to deliver a better experience to players”. It is very likely that this result will satisfy the publisher and the suit will be withdrawn, and the controversial game will come back online thoroughly changed.

Not everyone is “lucky” to be as big and as respectable as Ubisoft. It is therefore worthwhile to discourage others from cloning our game in advance, for example by securing rights to some of its elements. Regardless of the legal measures, it is also important to be aware of the danger and prepare for possible cloning of our title, for example by planning the game’s release cycle in such a way that the original game will appear on key markets first.